1955-1988 The Jernverk era

Political tug-of-war

“Certain national self-sufficiency issues are so important that a solution must be found, almost regardless of cost or financial risk. One of these issues is the iron problem,” wrote the Aftenposten newspaper in a leader in 1939. A government committee on iron had proposed constructing an iron and steel works and rolling mill at Mo i Rana. But the matter went back much further than this.

The iron problem

On 6 November 1900, Professor Johan H.L. Vogt gave a talk at the Polytechnic Association in Oslo in which he suggested the erection of an ironworks in Ofoten. Vogt was concerned to exploit Norwegian iron ore, and felt that in the long term an ironworks in the Dunderland valley would be a good idea. The iron problem had such a grip on the Norwegian imagination that in 1907 the Parliament appointed a committee to report on the “Question of electrometallurgical production of iron and steel”. Even at this time, Norwegian iron production was linked with Norway’s natural endowments of iron ore and water power.

AS Norsk Staal

The first serious plans for an ironworks in Rana appeared during World War I. At this time, the lack of steel was so threatening that two government committees were working on the problem. The first rolling mill, Norsk Blikkvalseverk near Bergen, was inaugurated in 1916. In the same year, engineers Emil Edwin and Hjalmar Johansen established AS Norsk Staal to develop a new method for producing soft, forgeable sponge iron in electric open-hearth furnaces. The company secured the rights to the ore in the Dunderland valley, while electric power was to be transferred from the government-owned Glomfjord power station. The concept was that the ironworks at Mo i Rana should “manufacture iron on a large scale in competition with European blast furnaces.” Norsk Staal encountered financial, technical and market-related problems, but the project could have been an interesting one. Edwin’s “Norwegian Steel Process” was in principle identical to the so-called HYL process, today reckoned among the best of the sponge iron manufacturing methods.

AS Norsk Jernverk

The political parties’ joint programme for 1945 puts in bluntly: “The iron problem must be solved”. The Ironworks Commission proposed that a Norwegian ironworks be constructed as soon as possible. By 1946, unlike in the 30’s, there was broad agreement that only the state was strong enough to bear the financial burden, estimated at 207 million kroner. On 10 July 1947, Parliament voted to erect a Norwegian ironworks. No members voted against the actual proposal, but a minority voted for a different location. In the debate, Minister of Trade Lars Evensen described the new ironworks as “the largest single industrial venture our country has ever embarked on.”

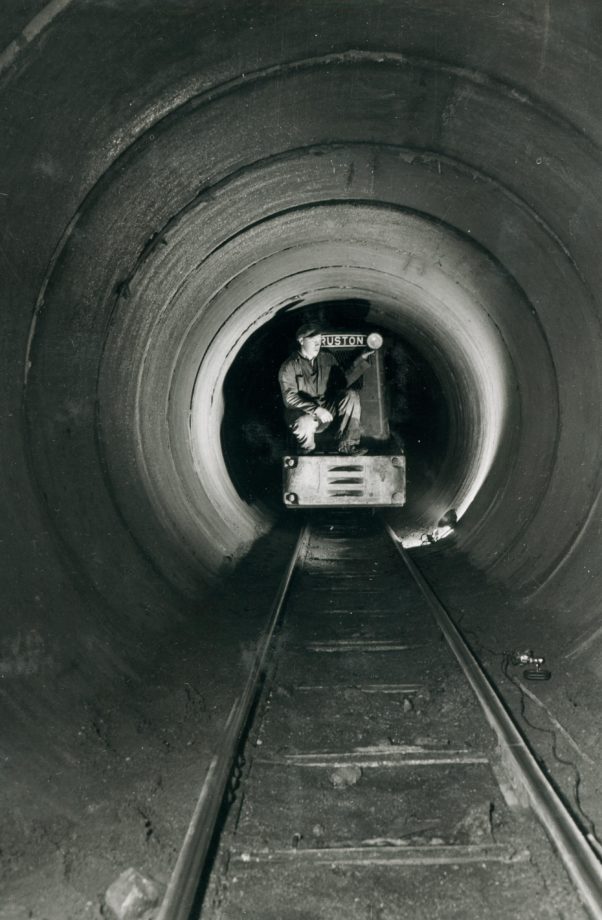

Construction period

Over seven years, an enormous infrastructure came into being. What was to become one of Norway’s largest industrial companies and one of the world’s most modern industrial complexes transformed forest scrub and heather into a development of several hectares extent. Water supply, power supply, drainage, an aqueduct system and a railway from the quay were just some of the facilities which had to be created before the construction of the actual crude iron works and shape rolling mill could start.

Construction of the ironworks took nine years (not three as originally planned); it cost 500 million kroner (not 250, while the 1945 report stipulated 207). Operations at Norsk Jernverk started in April 1955, when the strong post-war demand had significantly reduced, and with it, the price of iron and steel.

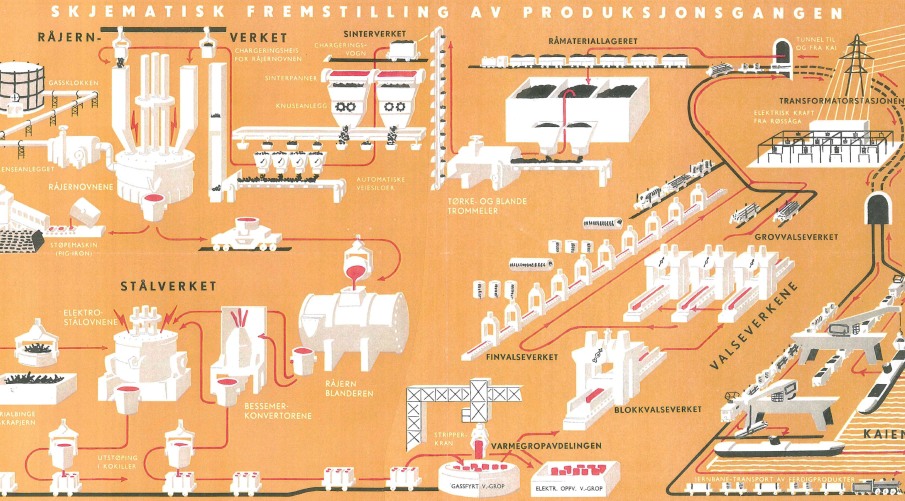

Presentation of the status of the ironworks

On 19 April 1955 at 22:05 hours, steel furnace 2 was tapped for the first time. 35 t molten steel ran down the tapping line into the teeming ladle. “A new province has been added to the country,” the Arbeiderbladet newspaper wrote in its leader column the next day. On 16 May, crude iron furnace 1 was tapped for the first time after 3 weeks of pre-heating.

Few of those involved had ever seen liquid iron and slag before. But the experienced crude iron works manager reported “an impressive effort from employees at the start-up of the world’s largest electric iron smelting furnace.” On 22 April, “the first steel blocks came dancing down the roller conveyor” to the first rolling stand in the cogging mill.

Roll setter Odd Myrvold was in position: “I well remember the first slab, and from the time it started its passage through the roll pair until it left us the process lasted about a quarter of an hour. Today the same operation takes just a few minutes”, he related with pride in the magazine Vårt Verk in 1959. Myrvold was among the key personnel whom the company had sent for further training. First at Surehamar Ironworks in Sweden, then a year in the USA and finally a period in Scunthorpe in Britain. Other employees spent time at Spigerverket in Oslo or in Germany or Britain.

Schematic representation of the process

Modern Rana takes shape

In 1923, the settlement of Mo, a landing place with 1450 inhabitants occupying over three square kilometres, was given a separate identity, though hemmed in on all sides by the extensive Nord-Rana district. Professor Sverre Pedersen drew up a town plan on garden city principles, with streets winding through the idyllic countryside and a town centre forming a main axis from the future railway station to the future civic park.

The feeling was one of optimism. But in the interwar period, both Mo and Nord-Rana were desperately poor. At times, one able-bodied person in three was unemployed. The mines provided some improvement and the Nordlandbane railway brought a certain amount of prosperity towards the end of the 1930’s. But when large-scale industry arrived, the people received it with open arms.

In 1939, Mo municipality seemed set to become a trading and manufacturing town of about 5000 inhabitants. But the Jernverket ironworks swept aside all plans and visions, and exploded the boundaries of the small community. In just 20 years, the population of Mo and Nord-Rana tripled from more than 8000 to more than 26,000. The town of Mo doubled in size twice, first between 1946 and 1949 and then between 1950 and 1960.

The home of Jernverket acted as a dam for the flood of migrants from Northern Norway. From far and near, people streamed into Mo to work on the erection of Jernverket. In the early years, well over half the construction workers were from Mo and Nord-Rana. 1952 was a record year with 568 new employees, all involved in the erection of the factory buildings and the fitting out of furnaces and rolling mill. In 1952, 60 of the newcomers were from Southern Norway and 236 from Northern Norway, many of them fishermen from the Helgeland coast.

Out of the workforce of 1400 who started operation of Jernverket in 1955, a large proportion were under 40 and only 200 were unmarried. Housing shortages soon became apparent, as so many families flooded into Mo. Initially, many made their home in the German hut settlements, which were converted into flats, with water laid on but no sewerage. Next, attention turned to building the ironworks estate village.

Somewhat unwillingly, Jernverket became the largest housebuilder in Mo – exceeding the efforts of the MoBo Building Society. In the period from 1949 to 1955, the company erected 504 homes for blue and white collar workers. 900 family flats received support in the form of subsidies, loans or materials. In all, Jernverket invested 30 million kroner in housing up to the mid-fifties. The company provided over 10,000 kroner in subsidies to each dwelling it erected, far more than any other Norwegian industrial enterprise had achieved. The company also provided a number of residential streets with water, sewerage and asphalt, and extended the hospital. Electricity and drinking water all issued from Jernverket for the benefit of Mo i Rana.

The ideal home for house builders was a detached house surrounded by a large garden, as sociologists visiting from Oslo to study “the great social changeover” in Nordland county could report. Their terse conclusion was that the ideal urban community without class divisions had made way for economic realities. Jernverket was without doubt a step up for the Rana district. But rapid urban growth produced an unbalanced age structure and a community which long had an unfinished appearance. Industry brought prosperity and a future but also a labour market characterised by one-sidedness and vulnerability. The fates of Jernverket and Rana were inextricably entwined.

The working day at Jernverket

Of the 750 or so workers who started operations at Jernverket in April 1955, only 60 or 70 had industrial experience. Most came to Mo from farms, smallholdings and fishing boats round about. Sceptical voices had warned against locating Jernverket in Northern Norway for this very reason, because it would take a generation to remake the small fisherman into a steelworker. Not everyone could get on with the necessary shiftwork and the discipline of industrial work. But the new ironwork employees were used to improvisation and independence, so the change went much better than the pessimists had predicted. Jernverket’s first years of operation were “a tale of hard work, disappointment and dedicated commitment.” In the steelworks the steel poured over floors, wagons and railway tracks. Sometimes the converters would not behave as they should, but started up without anyone touching them.

Further sources on the industrial history of Rana

– Ore, power and people: the history of Rana 1890-2005 / Hilde Gunn Slottemo 2007 (In Norwegian)

– How we made the steel: film memories of Jernverket and Mo i Rana, from construction, operation, family life and leisure (Norwegian film) 2010

– Dust, dirt and soot – a labour history view of sex and cultural barriers: part II / Hilde Gunn Slottemo 2010 (in Norwegian)

– We make steel : Jernverket Club 50th anniversary / Inger Bjørnhaug 2005 – Ironworks and social change: 13 contributions to the history of Jernverket and Mo i Rana / Per Maurseth, Håkon With Andersen, Anne Kristine Børresen (eds.) (in Norwegian) 2003

-Dreams of steel: A/S Norsk Jernverk from the 1940’s to the 1970’s/ Anne Kristine Børresen 1995 (in Norwegian)

– Norsk Jernverk 1946-1988 : from faith to fall/ Odd Chr. Gøthe 1994 (In Norwegian)

– Coke, workclothes and liniment: Mo Chemical Workers Association 1959-1990 : and about Norsk koksverk A/S / Per Karstensen 1991 (in Norwegian)

– Melting pot / Tor Jacobsen 1989 (in Norwegian)

Ruth Selnes og Bodil Graven forteller om arbeidet i Norsk Jernverk

«….As a non-specialist, I was impressed, amazed and rather proud that Norway possesses an industrial plant of this nature. If you could follow your products and see how they make life lighter and easier for people, you would better understand how useful your work is.»

Prime Minister Gerhardsen addressing the ironworks employees on 4 July 1960.